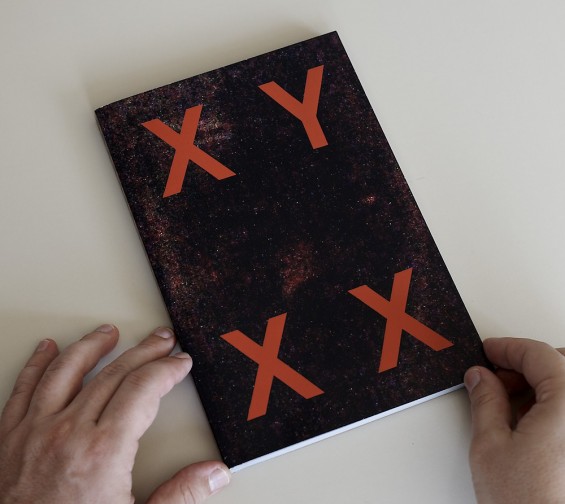

Fosi Vegue, XY XX, Dalpine, Madrid, 2014

The team responsible for last year’s highly acclaimed Karma — the publisher Dalpine and designer Eloi Gimeno — have returned with Fosi Vegue’s XY XX, in which the photographer shoots with his telephoto lens, through the window of a room across a courtyard, the sexual encounters of prostitutes.

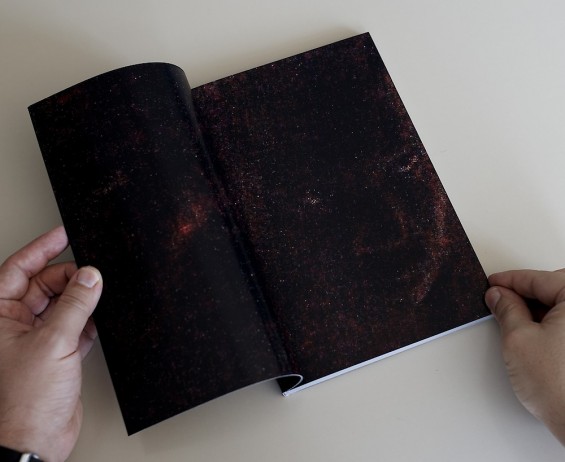

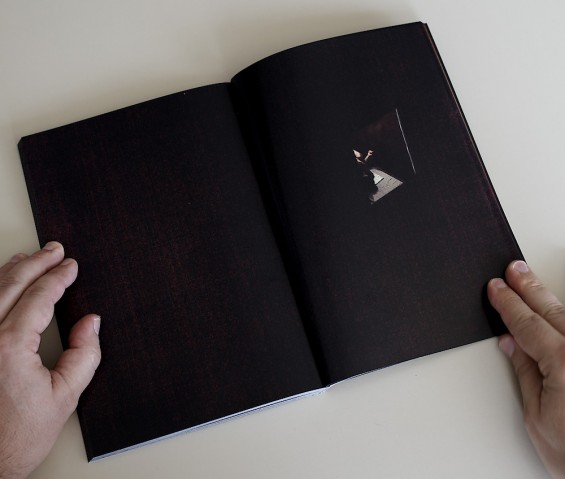

XY XX begins with what looks like a black background with scattered digital noise. If you push the book away from you, look at it sideways, and squint, you may notice that those clumps of white pixels aren’t random at all, they are eyes looking straight back at you. The image appears as a surprise, and it seems to come straight out of a nightmare. It is repeated in the next few pages until the eyes look away.

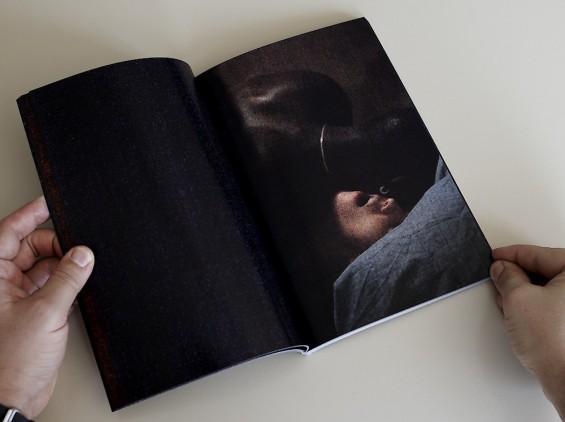

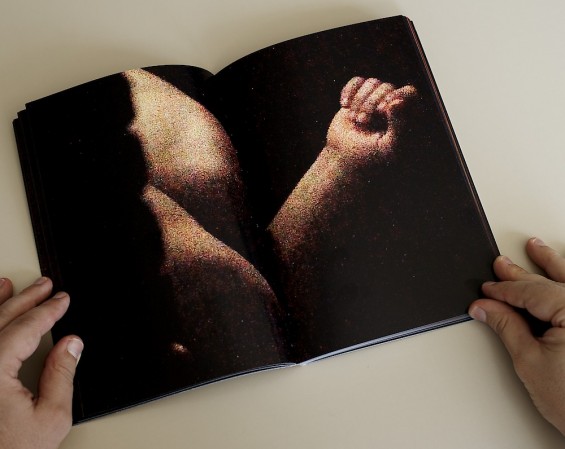

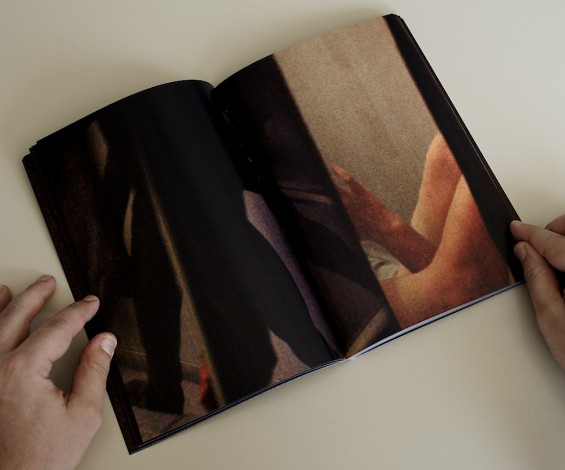

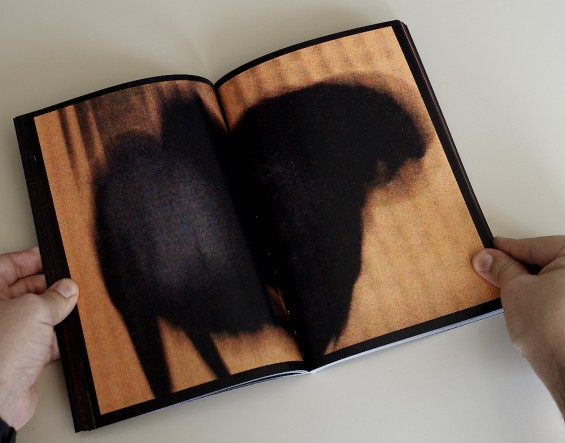

What follows is a series of photographs of the events inside the room. Sometimes we are far away and we can barely see what happens; sometimes we are thrown into bed with the action, we can feel the heat and almost touch the bodies. Some images return making you go back and look again, throwing temporal coherence into disarray. Midway through the book the images become more abstract, and the photographer points his camera at the clouds in the sky lit by scattered city light. I wont spoil the ending, let’s just say there are a couple of surprises lying in wait.

Perhaps the best known book of this type is Merry Alpern’s Dirty Windows, published in 1995. It is instructive to consider the differences and see where photography has gone in these past couple of decades.

Merry Alpern photographs through the back window of a sex club in Wall Street. The point of view is fixed. You see the window frame in every image separating the photographer / spectator from the action, which is almost always very clear: you see the hands, the faces, the money, the drugs, the sex. In contrast, in XY XX, the point of view floats, unmoored, in space; the images are cryptic, and, as Fosi Vegue says, they have to be deciphered by the reader who might imagine, rather than see, what is in them. The last traces of a humanist photography have vanished. Even the title reduces everything to the scientific codes for the chromosomes whose genes, when expressed, give rise to sexual difference in humans.

The elephant in the room is, of course, how in this day and age of full frontal assault on the western capitalist colonial hetero-patriarchal male gaze this book manages to press all the wrong buttons. Fosi Vegue says he wants to show the underbelly of society, that which is hidden. I don’t buy it. It would be like photographing stacks of dollar bills to show the workings of capitalism. Besides, in the country where the photographs were taken prostitution is advertised with large, colorful neon signs visible from miles away.

Reading this book I always come back to the interdependence of private space and public space. Like Spanish philosopher José Luis Pardo likes to point out, they need each other to exist. In a dictatorship, for example, where nothing is private and everything seems public, nothing really is, because everything is the private space of the dictator. In this book, an all seeing eye obliterates private space and leaves no room for politics.

Fosi Vegue

XY XX

published by Dalpine in Madrid, Spain;

first edition, 2014; 108 pages; 241 × 161 mm.;

softcover; perfect binding; edited by Fosi Vegue and Eloi Gimeno; designed by Eloi Gimeno; prepress by Victor Garrido; Printed in Artes Gráficas Palermo;